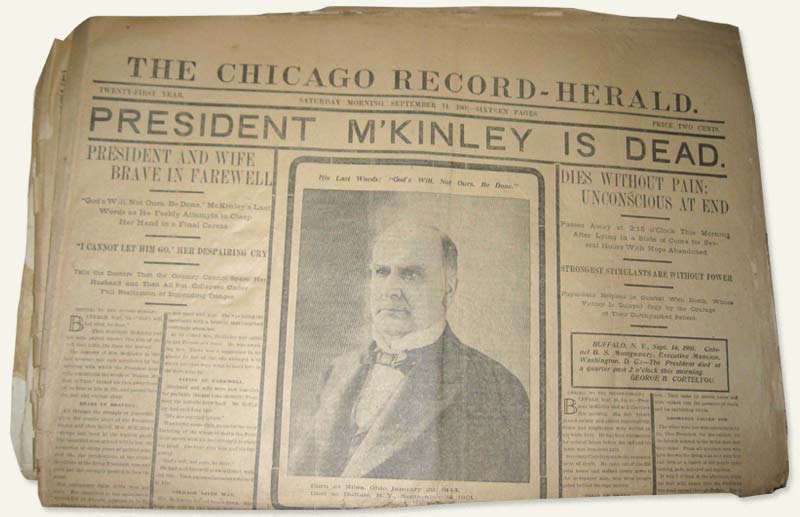

William McKinley was president in 1898-99, the time period of A Violet Season, but he was not to live much longer. This newspaper was among several my father’s family saved. He passed it on to me while I was researching the novel. Though McKinley’s assassination occurred two years after the time of the novel, it was fascinating to see and hold one of the actual newspapers that announced his death on September 14, 1901. The subheading reads: “President and Wife Brave in Farewell. ‘God’s Will, Not Ours, Be Done,’ McKinley’s Last Words as He Feebly Attempts to Clasp Her Hand in a Final Caress. ‘I Cannot Let Him Go,’ Her Despairing Cry.” Incidentally, the price of the paper was two cents.

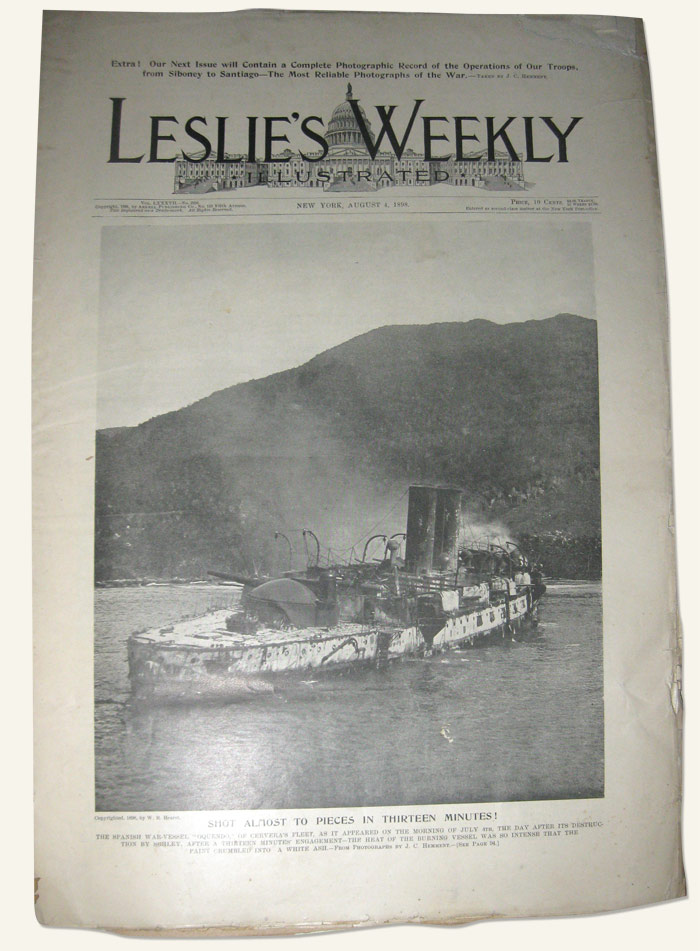

This copy of Leslie’s Weekly Illustrated was also passed down through our family. The caption of this front page, dated August 4, 1898, reads: “Shot Almost to Pieces in Thirteen Minutes! The Spanish war-vessel ‘Oquendo,’ of Cervera’s fleet, as it appeared on the morning of July 4th, the day after its destruction by Schley, after a thirteen minutes’ engagement—The heat of the burning vessel was so intense that the paint crumbled into a white ash.”

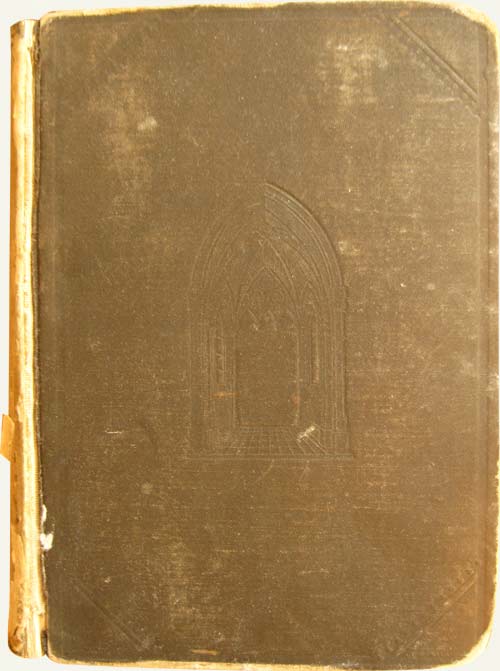

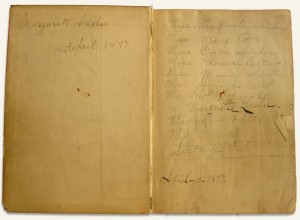

This hymnal represented a turning point in my research for A Violet Season. Until I borrowed this from my father to look up the hymns that might have been sung in Ida’s church, I had imagined I was writing a “historical” novel. Then I saw the list of names inside. My father’s best guess is that they are the names of the choir members in 1897. Among them is Grace Lasher, who was a young woman at the time, about the age of Alice. I knew her as Mrs. Brenzel, an elderly member of our church in the 1970s. She died when I was six or seven years old, but I remember her and her outgoing personality well. Seeing her maiden name–the name she had before she married and lost her first husband and then married Mr. Brenzel–inside that 1897 hymnal with the battered cover and the brittle pages told me that I wasn’t writing “history.” I was writing about people just like the real people I had known as a child, and my time was part of theirs.

This photocopied map, dated 1899, is from my copy of Jacob Riis’s classic book How the Other Half Lives. I used it to walk the Lower East Side on a couple of research trips to New York City. Some of the buildings on Riis’s map are still there today: a famous synagogue on Eldridge Street, a public school at the corner of Hester and Orchard, a fire station on Broome Street.

This photocopied map, dated 1899, is from my copy of Jacob Riis’s classic book How the Other Half Lives. I used it to walk the Lower East Side on a couple of research trips to New York City. Some of the buildings on Riis’s map are still there today: a famous synagogue on Eldridge Street, a public school at the corner of Hester and Orchard, a fire station on Broome Street.

On my second trip, I used the map to walk exactly as my characters do in one scene and took notes on what I saw. I also wanted to be sure that the addresses I used didn’t belong to a business or someone’s home today.

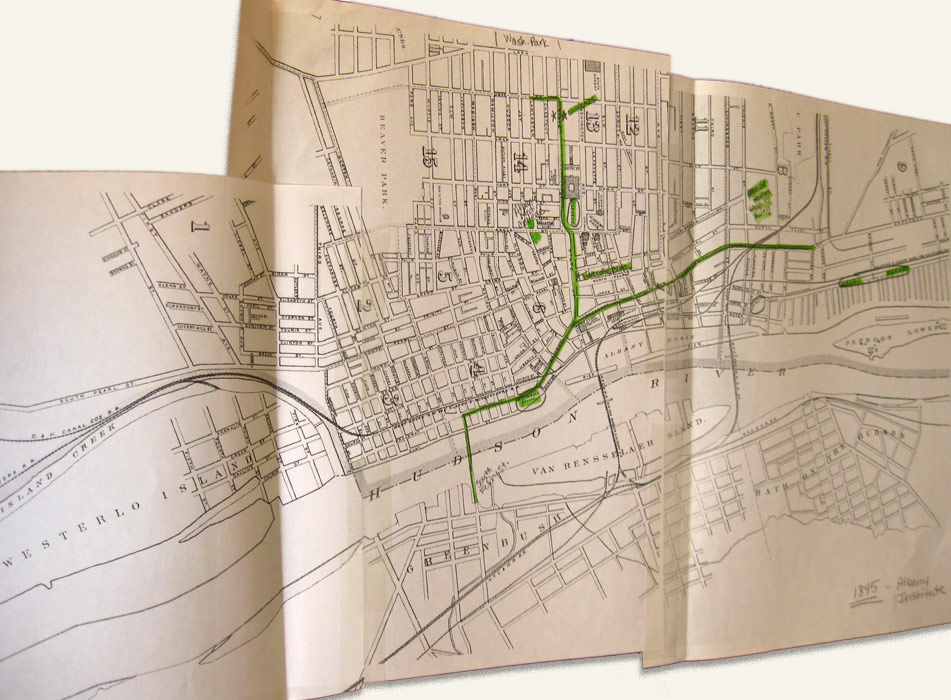

When I visited the wonderful Albany Institute of History and Art, I asked the volunteers if they had a map of Albany in 1899. It took some searching, but eventually they emerged from storage with a gigantic five-foot-long 1895 map rolled up on a cart. From it, we all learned that a particular bridge had already been built at that time and my characters would no longer have had to cross the Hudson River by ferry. Staffers managed to make this photocopy for me, and I traced the route my characters would take into the city.

This dress, given to me by my aunt, is believed to have been my great grandmother’s. I have it because I was named for her. The waist of the skirt measures only 19 ½ inches, but the length is exactly right for me, suggesting that we may have been the same height. Love letters written by my great grandparents during their engagement in 1890-91 helped me get the voice right in the letters between my characters, and I stole from my great grandfather the sweet closing: “I remain yours, Joe.”

This dress, given to me by my aunt, is believed to have been my great grandmother’s. I have it because I was named for her. The waist of the skirt measures only 19 ½ inches, but the length is exactly right for me, suggesting that we may have been the same height. Love letters written by my great grandparents during their engagement in 1890-91 helped me get the voice right in the letters between my characters, and I stole from my great grandfather the sweet closing: “I remain yours, Joe.”

This is the gravestone of John H. Irvis, a decorated member of Company B, 26th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry, Civil War. Buried in the cemetery at St. John’s Reformed Church in Upper Red Hook, NY, he is the inspiration for a character mentioned in passing in the novel. That character, named Walker, was killed during the Civil War, though Mr. Irvis survived the war and died in 1903. Although no major characters in the novel are African-American, I wanted to include a nod to the fact that blacks and whites were worshiping together at that time and also to the sacrifices that many black men made for their country in time of war. Although he worshiped at an integrated church and was buried in an integrated churchyard, Mr. Irvis faced the usual Northern prejudices of the time. He spent his last days at the New York Colored Hospital.